Whoosh, whoosh, whoosh all the way down the mountain for 15 odd kilometers.

Ok maybe it was more like bump, curse, bump. The rock-strewn Daxuenshan Pass road was rough, and we maxed out at around 8 kms an hour. Still, it was fun to finally be going DOWN after such an arduous ride up.

The valley below was heavily cultivated and dotted with stately Tibetan homes made of rammed earth. I’d imagined a massive feast in the Ranwu, first town we encountered– but alas there wasn’t much to be had in either the dusty shop or dark, dank village restaurant.

After an unsatisfying bag of obnoxiously sweet industrial cupcakes, we were on our way: destination Xiangcheng.

At an altitude of around 2,800 meters, the sun was as intense as that of the Sahara or the Australian outback. Soon it was time to start peeling off the layers. It felt good not to be cold.

Our bikes and bodies had performed admirably on the demanding Daxuenshan Pass. We were in high spirits, and ready to take on the many epic climbs that lay ahead.

And then, just as we were sprinting up the last hill into Xiangcheng, disaster struck. The makeshift headset failed. The steering was shot and I could barely control the bike. I ended up pushing the last few hundred meters into town.

What to do? Well, fill our growling stomachs for starters and then track town a cheap hotel and hit the shower.

Xiangcheng is a largish town that appears to be caught up in an economic boom. Hotels and housing projects are sprouting up and the center features a glitzy square with Las Vegas-style lighting. You’d think such a place would boast at least one bike shop. Not a chance.

Eric made the rounds to the various car mechanics in town, hoping one of them might be able to miraculously bring the headset back to life. All in vain.

The closest major city certain to have a bike shop, Chengdu, was a grueling 30-hour bus ride away. Roundtrip seemed an excessive amount of travel for a bike repair. Shipping sounded better. We contacted the friendly and helpful guys at Natookes Bike Shop. They could probably track down the necessary part and have it sent.

Hmph. Hanging around in our grubby hotel (with its shared toilet facilities in which someone seemed to have always just taken a crap with having the courtesy of flushing away the evidence) waiting for a part to arrive seemed equally unappealing. And we DEFINITELY didn’t want to give up and bus it all the way to Chengdu and miss the mountains we’d been dreaming of for so long.

As I pondered our dilemma and searched for a solution on the Internet, Eric slipped out to tinker with my bike.

Up and running again

An hour or so later he reappeared. “Take it for a spin and see if it’s ride-able.”

I complied. The steering was stiff and choppy, but I could maneuver the aging Koga. That’s all that counted.

“It’ll do,” was my verdict.

The next morning we rolled out of town in a thick fog and steady drizzle. Two big passes, the highest at 4,728 meters, and a couple hundred kilometers separated us from the Tibetan town of Litang.

The sub-optimal steering didn’t bother me too much. Any bike that’s endured 155,000 kilometers of fully-loaded riding develops a few rattles and shakes. I’m used to the gears not quite shifting as they should and squeezing really, REALLY hard on the brakes to bring the bike to a halt (sometimes I even resort to that elementary school trick of dragging my feet on the ground).

Time to admit defeat!

But just 30 kilometers out of Xiangcheng the steering completely gave out. Nearly impossible to ride on flat roads and utterly dangerous on a descent. Resurrecting the bike roadside was out of the question. We admitted defeat and decided to hitch a ride towards Litang, hoping for the best.

A fresh-faced Tibetan truck driver and his pretty young wife were the first ones to offer us a lift. We all squeezed into the brightly decorated cab of the truck and attempted communication. They both broke out into broad smiles when I recognized a photo of the Panchen Lama. (The Chinese government bans the display of images of the Dalai Lama.)

Our driver was cautious (by local standards) and took the switchbacks with care, blasting his horn to announce his presence as he edged around blind curves. He even drove extra slow while texting.

This first pass was not too spectacular, and the weather was lousy. We felt only a slight pinch of sadness that we weren’t doing it self-propelled.

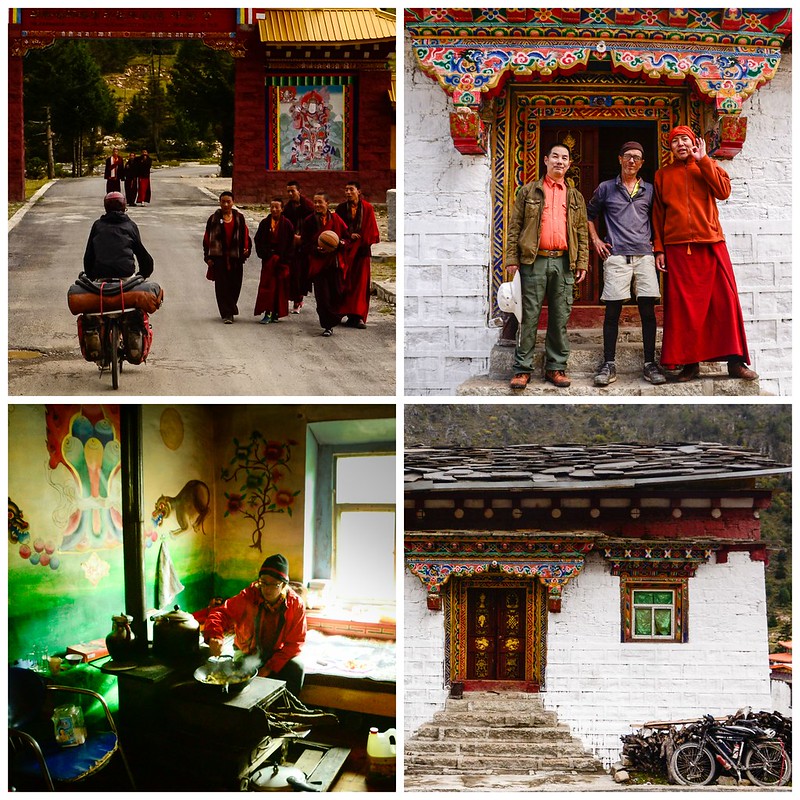

We were dumped off at a crossroads in Sangdui, midway to Litang. After wobbling up the highway a bit we came across a large group of novice monks tossing around a basketball. They motioned for us to continue up the road to their monastery. It was a beautiful collection of ancient stone buildings tucked away beneath the mountains. An older monk came out to greet us and eventually we were invited to spend the night. This surprised me as I understood the government keeps close tabs on Tibetan monks and frowns on them getting too close to foreigners (who might fill their heads with ideas of democracy and an independent Tibet).

The wood burning stove was fired up in a small cottage and we frittered away a lovely afternoon in our cozy surroundings.

The next morning we were back on the highway attempting to hitch a ride over Tuer pass and into Litang. Our opportunity came when a bus pulled over and disgorged its passengers for a roadside toilet stop.

Eric negotiated a ride with the driver and we were on our way. The morning was clear, Tuer Pass was gorgeous and our disappointment at missing the pass quite complete.

Getting high

At just over 4,000 meters, Litang is one of the highest cities in the world (400 meters higher than Lhasa). Many important Tibetan figures, including the 7th and 10th Dalai Lamas, hail from this remote city with a sub-arctic climate.

We were both in rather foul moods when we arrived. Eric was peeved about being overcharged by the unscrupulous bus driver and I was annoyed with my Koga for letting me down when I most needed her.

In all our years on the bike this is only the second time we’d had to resort to a bus (the first time was Christmas Eve in Patagonia when we were stranded in the middle of nowhere fighting a violent headwind and couldn’t bear the thought of spending the holiday in the sticks).

After settling into a nice clean room (excrement-free toilet down the hall) in a small hotel run by a Tibetan family,we directed our attention towards the offending headset.

Litang was a scruffy town, but larger than Xiangcheng. It’ also on the main Sichuan-Tibet highway, meaning hundreds of Chinese cyclists pass through on their way to Lhasa (foreigners, of course, aren’t permitted to travel any further up the highway into the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR).

With all those cyclists, we reasoned, Litang, just had to have a bike shop. Our ride through the mountains, after all, hinged on tracking down a headset.

A change of luck

Whether it’s good karma (we recently stopped to help a guy push out his vehicle after he got stuck on a muddy road) or just dumb luck, Eric managed to unearth the exact part we needed. Turns out Litang’s got a bike mechanic in a tiny workshop on the edge of town.

YIPPPEEE! We were good to go.

What an adventure.

And yes YIPPPEEEE for fixing that headset.

wonderful pics! what a place!

can i ask how did you cope with the bigest problem out there – and this is getting 90 days visa somehwere in south east asia. i know – from my own experience – that going into long haul distance cyling in eastern tibet with the 30 days visa is horrible, due to fact, that all you have to do is push push hard every day.

would appreciate the sharing of this knowledge

We were able to obtain 90 day single-entry visas for China in Kuala Lumpur. I don’t know if this is standard procedure when applying in Malaysia–perhaps we just got lucky. I realize most travelers are only able to get a 30 day visa for China and usually end up extending it once (we’ve heard the Chinese authorities rarely grant a second extension). Many cyclists who want to spend more time in China exit the mainland and go to Hong Kong, then applyfor new Chinese visa and re-enter mainland China.

Just found you guys. Really glad, too. Your photos are simply incredible. Thanks for sharing your travels.