update 9.

dust and drudgery in the sahel

27 December, 2006

Mali and Niger

Total kilometers cycled: 14,023

Total flat tires:- Eric: 19

- Amaya: 3

More than once during the past month we've

asked ourselves what on earth made us decide to cycle through Africa.

We've been plagued by ill-health, thorn-filled and

puncture-producing pistes

and growling stomachs, as Africa is no veggie heaven and we keep to a

steady diet of rice and beans with the occasional salad being the

culinary highlight. We strive to equanimously take

the good

with the bad, but, well, it's not always easy. Admittedly,

we

have passed through some stunning countryside and meandered through

some very exotic Sahelian markets, and African hospitality never fails

to impress us, but it would be nice if things got a bit easier!

More than once during the past month we've

asked ourselves what on earth made us decide to cycle through Africa.

We've been plagued by ill-health, thorn-filled and

puncture-producing pistes

and growling stomachs, as Africa is no veggie heaven and we keep to a

steady diet of rice and beans with the occasional salad being the

culinary highlight. We strive to equanimously take

the good

with the bad, but, well, it's not always easy. Admittedly,

we

have passed through some stunning countryside and meandered through

some very exotic Sahelian markets, and African hospitality never fails

to impress us, but it would be nice if things got a bit easier! Eric had been having breathing difficulties and feeling weak in general, and as we cycled through the dry savanna of eastern Guinea, the situation worsened. At one point, completely devoid of energy, he flung his bike by the side of the road and lay down under the scorching sun--trees had become a rarity--to rest. He was seriously considering flagging down a passing truck, when a local passer-by informed us that there was a hospital just ahead. Lo and behold, there was indeed a health

center,

although no one was about even though the door was wide open. No

worries, a crowd of local children quickly gathered to spy on the toubabs

and a couple of boys soon scampered off in search of the 'doctor'.

After noting Eric's ailments and briefly examining

him, the

young med student diagnosed him with another bout of malaria aggravated

by pneumonia which, according to him, had been induced by the dusty

roads. Now, our guidebook warns us about seeking medical

assistance in rural areas, where hygiene is likely to be dubious and

clinics ill-equipped, but the intern seemed competent enough and we

didn't really have a choice. The treatment consisted of an

IV,

which he insisted on administering outdoors under a shady tree.

This was surely for the entertainment of the local villagers,

who

never seemed to tire of watching white people. We spent the

night

at the clinic, and in the morning the village chief, having gotten wind

that toubabs

were in town,

came by to pay his respects. We're still not sure what sort

of a

concoction was in the IV, but it seemed to do the trick and Eric was

feeling well enough to cycle on to the next town.

center,

although no one was about even though the door was wide open. No

worries, a crowd of local children quickly gathered to spy on the toubabs

and a couple of boys soon scampered off in search of the 'doctor'.

After noting Eric's ailments and briefly examining

him, the

young med student diagnosed him with another bout of malaria aggravated

by pneumonia which, according to him, had been induced by the dusty

roads. Now, our guidebook warns us about seeking medical

assistance in rural areas, where hygiene is likely to be dubious and

clinics ill-equipped, but the intern seemed competent enough and we

didn't really have a choice. The treatment consisted of an

IV,

which he insisted on administering outdoors under a shady tree.

This was surely for the entertainment of the local villagers,

who

never seemed to tire of watching white people. We spent the

night

at the clinic, and in the morning the village chief, having gotten wind

that toubabs

were in town,

came by to pay his respects. We're still not sure what sort

of a

concoction was in the IV, but it seemed to do the trick and Eric was

feeling well enough to cycle on to the next town. The first thing that struck us In Mali was the harmattan,

the sometimes violent wind which blows down from the Sahara between

December and February

and smothers everything in a dusty haze. This is supposedly a

north-easterly wind, but we swear that no matter in which direction we

cycled, we were fighting a fierce headwind. This was tough on

morale and severely hampered our progress. One of our first stops in

Mali was the capital, Bamako, which was noisy and hectic like other

west African cities and had little to hold our interest. We

were

there to pick up visas and were quite astonished to find out that fees

are negotiable, well at least they were at Togo's consulate. The

friendly honorary consul gave us a steep discount and even telephoned

his counterpart at Niger's embassy to see if he would do the same for

his new 'friends'. The Nigerien consul was very apologetic,

but

unfortunately the best he could do was offer us a cup of coffee and

some insights into African mentality.

The first thing that struck us In Mali was the harmattan,

the sometimes violent wind which blows down from the Sahara between

December and February

and smothers everything in a dusty haze. This is supposedly a

north-easterly wind, but we swear that no matter in which direction we

cycled, we were fighting a fierce headwind. This was tough on

morale and severely hampered our progress. One of our first stops in

Mali was the capital, Bamako, which was noisy and hectic like other

west African cities and had little to hold our interest. We

were

there to pick up visas and were quite astonished to find out that fees

are negotiable, well at least they were at Togo's consulate. The

friendly honorary consul gave us a steep discount and even telephoned

his counterpart at Niger's embassy to see if he would do the same for

his new 'friends'. The Nigerien consul was very apologetic,

but

unfortunately the best he could do was offer us a cup of coffee and

some insights into African mentality.  After the capital, we headed northeast

towards the Inland Delta region, and couldn't help feeling that we were

making a huge detour as we returned towards Europe and saw the distance

from Cape Town growing rather than diminishing. Most of Mali

lies within the Sahel, the desolate zone bordering the Sahara where the

desert is fast encroaching. There is little that grows in

such an

arid region and vegetation is mostly limited to acacia and pesky thorn

trees. The later of which perhaps explain Eric's prolific

punctures, although it's a mystery as to why Amaya's tires have fared

so much better. The landscape is largely monotonous and the

kilometers seemed to pass painfully slowly. Settlements are spaced far

apart and finding water and food was a real concern.

Fortunately, this landlocked country has been blessed with some

outstanding geographical features to break up the monotony of the flat

plains and scruffy bush. 1,300 kilometers of the Niger river

run

through Mali and the sheer mesas and craggy rock formations found near

Hombori have been compared to those in Monument Valley. The

walled villages along the river are in the Sudanic style, molded from

the grey clay of the surrounding flood plain.

After the capital, we headed northeast

towards the Inland Delta region, and couldn't help feeling that we were

making a huge detour as we returned towards Europe and saw the distance

from Cape Town growing rather than diminishing. Most of Mali

lies within the Sahel, the desolate zone bordering the Sahara where the

desert is fast encroaching. There is little that grows in

such an

arid region and vegetation is mostly limited to acacia and pesky thorn

trees. The later of which perhaps explain Eric's prolific

punctures, although it's a mystery as to why Amaya's tires have fared

so much better. The landscape is largely monotonous and the

kilometers seemed to pass painfully slowly. Settlements are spaced far

apart and finding water and food was a real concern.

Fortunately, this landlocked country has been blessed with some

outstanding geographical features to break up the monotony of the flat

plains and scruffy bush. 1,300 kilometers of the Niger river

run

through Mali and the sheer mesas and craggy rock formations found near

Hombori have been compared to those in Monument Valley. The

walled villages along the river are in the Sudanic style, molded from

the grey clay of the surrounding flood plain.  We

followed some minor gravel roads and tried to follow the scenic river

and its inland delta as much as possible. A highlight was our

stay

in Djenné, with its Grand Mosque and animated Monday market.

At dawn, farmers and merchants from far-off villages arrived

via

the river in wooden pirogues

and starting spreading out their wares on the central

square.

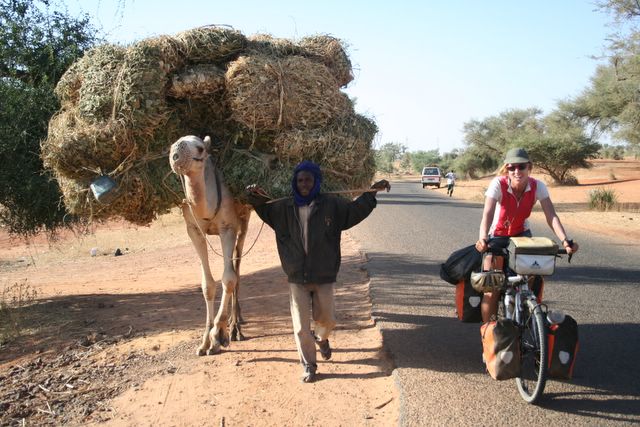

The melange of different ethnic groups--Moors in their flowing robes,

Peul with their pointy hats and the nomadic Tuareg on their camels

meant people watching was top on the list of activities.

We

followed some minor gravel roads and tried to follow the scenic river

and its inland delta as much as possible. A highlight was our

stay

in Djenné, with its Grand Mosque and animated Monday market.

At dawn, farmers and merchants from far-off villages arrived

via

the river in wooden pirogues

and starting spreading out their wares on the central

square.

The melange of different ethnic groups--Moors in their flowing robes,

Peul with their pointy hats and the nomadic Tuareg on their camels

meant people watching was top on the list of activities. Next, we found ourselves in Bandiagara, on the Dogon Country tourist track, being hassled by potential guides wanting to organize a trek for us to visit the cliffside villages and learn more about the ancient Dogon customs. We were in no mood to be hassled as our 63-kilometer ride to Bandiagara had been the most taxing to date. The piste we chose to take--30 kilometers shorter than following the paved road--was a barely visible sand trap branching off in so many directions that its a miracle we found our way to Bandiagara. We spent a good part of the day pushing the bikes, pulling out thorns, and for Amaya, shedding a few tears. Eric was busy repairing punctures and coaxing Amaya to get back on her bicycle! It felt like the end of the world and we were mighty happy to reach 'civilization' again and down a refreshing coca-cola.

The 150 euro asking price for a three-day trek seemed ridiculously high, so we decided to cycle down to the escarpment and organize local guides in individual villages. This turned out to be a wise decision and we were able to do some rooftop camping and hike up the cliffs to visit the ancient dwellings and learn all about the customs from one of the chief's sons. All we missed out on by not going on an organized trek was the 30 kilometer ride in the 4WD and our self-organized trek cost just 30 euros.

Hombori

was our next destination and there were some truly stunning stretches

of road as we passed by the pinnacles of the sandstone rock formations.

Along the way, we camped with local families and were kept awake by the

donkeys braying, cows mooing, goats butting horns and chickens cackling

just outside our tent. The villagers greeted us

enthusiastically and one day we were amazed to see a group of some 15

boys, all clad in blue loincloth, wielding a stick and covered in a

layer of dust, rush out to greet us. They had recently

undergone

a circumcision ceremony and were in the care of a marabout (holy man).

The sticks and layer of earth were to ward off evil spirits

who

might attack the boys.

Hombori

was our next destination and there were some truly stunning stretches

of road as we passed by the pinnacles of the sandstone rock formations.

Along the way, we camped with local families and were kept awake by the

donkeys braying, cows mooing, goats butting horns and chickens cackling

just outside our tent. The villagers greeted us

enthusiastically and one day we were amazed to see a group of some 15

boys, all clad in blue loincloth, wielding a stick and covered in a

layer of dust, rush out to greet us. They had recently

undergone

a circumcision ceremony and were in the care of a marabout (holy man).

The sticks and layer of earth were to ward off evil spirits

who

might attack the boys.  After

Hombori, the scenery reverted to featureless flatlands and it was time

again for the MP3 player. By the time we reached Gao, and finally

turned

south (this felt like progress again!) we had covered almost 1,500

kilometers. It had been a trying journey, mostly due to the

monotony of the land, and we were looking forward to the trip south to

Niamey. Our guidebook claimed that the road hugged

the Niger

river, passing through numerous picturesque fishing villages and the

Michelin map had classified the 450-kilometer stretch as a scenic

route. Locals told us that, although the road was not yet

entirely paved, the foundations were in place, the sand had been

cleared and cycling would be easy enough. What a disappointment when

just a few kilometers outside of Gao the road turned into a sandy track

and we were again pushing the bikes as 4-wheel drives flew by kicking

up a storm of dust in their wake. Masks are a common

accessory

for motorcyclists in Mali and Eric donned his, which offered some

protection. Nevertheless, cycling was extremely unpleasant

and we

were hardly enjoying the scenic route. Just when it seems

that

things can't get worse, they can. The route rarely 'hugged

the

banks' of the river and we saw plenty of signposts for those

'picturesque villages' indicating that they lay several kilometers down

sandy tracks, and we were hardly in the mood for detours.

Time

for a confession. One desperate morning, when we could really

no

longer stand pushing the bikes through the deep, soft sand we

loaded them into the back of a pickup and rode in

air-conditioned

comfort the last 100 kilometers to the Niger border. From

there

it was back in the saddle . The road and the scenery improved

dramatically and after 50 kilometers we were back on

tarmac.

After

Hombori, the scenery reverted to featureless flatlands and it was time

again for the MP3 player. By the time we reached Gao, and finally

turned

south (this felt like progress again!) we had covered almost 1,500

kilometers. It had been a trying journey, mostly due to the

monotony of the land, and we were looking forward to the trip south to

Niamey. Our guidebook claimed that the road hugged

the Niger

river, passing through numerous picturesque fishing villages and the

Michelin map had classified the 450-kilometer stretch as a scenic

route. Locals told us that, although the road was not yet

entirely paved, the foundations were in place, the sand had been

cleared and cycling would be easy enough. What a disappointment when

just a few kilometers outside of Gao the road turned into a sandy track

and we were again pushing the bikes as 4-wheel drives flew by kicking

up a storm of dust in their wake. Masks are a common

accessory

for motorcyclists in Mali and Eric donned his, which offered some

protection. Nevertheless, cycling was extremely unpleasant

and we

were hardly enjoying the scenic route. Just when it seems

that

things can't get worse, they can. The route rarely 'hugged

the

banks' of the river and we saw plenty of signposts for those

'picturesque villages' indicating that they lay several kilometers down

sandy tracks, and we were hardly in the mood for detours.

Time

for a confession. One desperate morning, when we could really

no

longer stand pushing the bikes through the deep, soft sand we

loaded them into the back of a pickup and rode in

air-conditioned

comfort the last 100 kilometers to the Niger border. From

there

it was back in the saddle . The road and the scenery improved

dramatically and after 50 kilometers we were back on

tarmac. Christmas eve was spent in the compound of some American Baptist

missionaries in Ayorou. Our image of missionaries, we now

realize, was severely out-dated. We imagined them 'living like the

natives' in mud huts and cooking over open fires while preaching the

gospel. Our modern missionaries came to greet us in their

Toyota

4WD and let us pitch our tent outside their air-conditioned

home--complete with flushing toilets, running water, satellite TV and

an American-style kitchen. Ayorou is famous for its colorful regional

market, attracting traders from as far off as Nigeria and Burkina Faso.

After an early morning pirogue trip to see the hippos

upstream,

we wandered around the stalls and checked out the bustling livestock

market which was doing a brisk business thanks to the upcoming Tabaski

(New Years) celebrations. Well-to-do families are meant to

slaughter a ram and share it with those less fortunate. Mini-buses were

being loaded up with the animals strapped on the roof for transport

back to surrounding towns and villages.

Christmas eve was spent in the compound of some American Baptist

missionaries in Ayorou. Our image of missionaries, we now

realize, was severely out-dated. We imagined them 'living like the

natives' in mud huts and cooking over open fires while preaching the

gospel. Our modern missionaries came to greet us in their

Toyota

4WD and let us pitch our tent outside their air-conditioned

home--complete with flushing toilets, running water, satellite TV and

an American-style kitchen. Ayorou is famous for its colorful regional

market, attracting traders from as far off as Nigeria and Burkina Faso.

After an early morning pirogue trip to see the hippos

upstream,

we wandered around the stalls and checked out the bustling livestock

market which was doing a brisk business thanks to the upcoming Tabaski

(New Years) celebrations. Well-to-do families are meant to

slaughter a ram and share it with those less fortunate. Mini-buses were

being loaded up with the animals strapped on the roof for transport

back to surrounding towns and villages. We rolled into Niamey Christmas Day and are spending a few days at the Catholic Mission enjoying some time off the bikes. Next comes Burkina Faso and visits to some of its national parks for animal spotting. Keep your fingers crossed for smooth roads and tailwinds!