update 7.

welcome to africa!

12 October, 2006

Nouakchott, Mauritania to Ziguinchor, Senegal via The Gambia

Heading

south from the Mauritanian capital in mid September the desert

gradually gave way to dry savanna and bush and as we neared the

Senegal border the countryside took on an ever more tropical feel.

After the solitude of the Sahara, passing the simple compounds of

mud-brick huts and watching the daily goings-on of the villagers was a

welcome distraction. As the afternoon temperature rose, groups

gathered for a chat or a snooze under shady trees and many called out

to us to come and have a rest. Having an entirely different

conception of time and urgency, they were clearly baffled when we

politely declined their offers, explaining our rush to reach the border.

Heading

south from the Mauritanian capital in mid September the desert

gradually gave way to dry savanna and bush and as we neared the

Senegal border the countryside took on an ever more tropical feel.

After the solitude of the Sahara, passing the simple compounds of

mud-brick huts and watching the daily goings-on of the villagers was a

welcome distraction. As the afternoon temperature rose, groups

gathered for a chat or a snooze under shady trees and many called out

to us to come and have a rest. Having an entirely different

conception of time and urgency, they were clearly baffled when we

politely declined their offers, explaining our rush to reach the border.  We arrived in the frontier town of Rosso just as the sun was setting

and perhaps it was just as well since the dimness masked some of the

town's squalor and filth. Border towns are often dodgy places full of

shady characters looking to make a quick buck on black market goods or

dubious deals changing money, and Rosso was no exception. The

immigration office having closed down for the day, we took a room in

the town's tourist class hotel after Amaya turned her nose up at the

budget accommodation which offered a dingy room with a couple of bare

mattresses on the floor, leaky plumbing and the distinct oder of greasy

food wafting up from the eatery below. Cost cutting has its limits.

We arrived in the frontier town of Rosso just as the sun was setting

and perhaps it was just as well since the dimness masked some of the

town's squalor and filth. Border towns are often dodgy places full of

shady characters looking to make a quick buck on black market goods or

dubious deals changing money, and Rosso was no exception. The

immigration office having closed down for the day, we took a room in

the town's tourist class hotel after Amaya turned her nose up at the

budget accommodation which offered a dingy room with a couple of bare

mattresses on the floor, leaky plumbing and the distinct oder of greasy

food wafting up from the eatery below. Cost cutting has its limits. Crossing the border proved trying. After being allowed behind the port barricade a uniformed official snatched our passports and disappeared without a word. We were herded on to the overcrowded ferry and wedged in between the vehicles, still wondering what had happened to the immigration agent. He appeared sometime later and demanded 20 euros for the 'formalities'. We had no intention of contributing to corruption, so under the guise of just wanting to have a look at the exit stamps, Amaya snatched back the passports and quickly hid them safely in her money belt. Seeing his chances for a hefty bribe greatly diminished, the official became livid and insisted we disembark immediately. We ignored his clamors and eventually he gave up insisting we pay the formality fee, surely sensing our resolve not to part with any of our cash.

Once

across the border a quiet backroad meandered through lush countryside

dotted with acacia trees and in each village we passed we were greeted

with enthusiastic shouts of 'Toubab', as whites are referred to in

these parts. We weren't used to causing such a stir and by the

end of the day we were hoarse, having tried to match the locals'

exuberant greetings village after village in a fairly heavily populated

area. Our first stop in Senegal was the former French capital,

St. Louis. The houses are crumbling but the town still has a bit

of flair and the surrounding wetlands made for a pleasant enough

excursion. We ended up spending several days in St.Louis waiting

for the customs agent at the post office to return from his holiday, so

the backlog of parcels could be inspected and we could finally pick up

our long-awaited package containing new tires. Patience folks,

this is Africa!

Once

across the border a quiet backroad meandered through lush countryside

dotted with acacia trees and in each village we passed we were greeted

with enthusiastic shouts of 'Toubab', as whites are referred to in

these parts. We weren't used to causing such a stir and by the

end of the day we were hoarse, having tried to match the locals'

exuberant greetings village after village in a fairly heavily populated

area. Our first stop in Senegal was the former French capital,

St. Louis. The houses are crumbling but the town still has a bit

of flair and the surrounding wetlands made for a pleasant enough

excursion. We ended up spending several days in St.Louis waiting

for the customs agent at the post office to return from his holiday, so

the backlog of parcels could be inspected and we could finally pick up

our long-awaited package containing new tires. Patience folks,

this is Africa! Dreaded Dakar, notorious for congested roads, pushy street

vendors and oppressive heat, was our next stop. In fact, we would

gladly have avoided the capital entirely, but a need to pick up a

visa for The Gambia necessitated a visit. We made the best of

things and chose to stay in the nearby fishing village of Yof rather

than in the heart of one of West Africa's mega-cities. From the

terrace of the guesthouse we watched the sunrise over the Atlantic and

peered down at the hustle and bustle as the fisherman set off in their

motorized pirogues. Late afternoon the beach was again abuzz with

activity as the men returned with the daily catch, fishmongers

vied for customers and boys tossed around a soccer ball among the stout

women gutting the tuna and barracudas. This being the month of

Ramadan, and the region being predominately Muslim, fasting is the norm

for most people from sunrise to sunset. Restaurants are open but

we're often the only customers and invariably the only thing on

offer is Chep-bu-jen--fish and rice. Delicious the first 20 times, but after that a bit monotonous.

Dreaded Dakar, notorious for congested roads, pushy street

vendors and oppressive heat, was our next stop. In fact, we would

gladly have avoided the capital entirely, but a need to pick up a

visa for The Gambia necessitated a visit. We made the best of

things and chose to stay in the nearby fishing village of Yof rather

than in the heart of one of West Africa's mega-cities. From the

terrace of the guesthouse we watched the sunrise over the Atlantic and

peered down at the hustle and bustle as the fisherman set off in their

motorized pirogues. Late afternoon the beach was again abuzz with

activity as the men returned with the daily catch, fishmongers

vied for customers and boys tossed around a soccer ball among the stout

women gutting the tuna and barracudas. This being the month of

Ramadan, and the region being predominately Muslim, fasting is the norm

for most people from sunrise to sunset. Restaurants are open but

we're often the only customers and invariably the only thing on

offer is Chep-bu-jen--fish and rice. Delicious the first 20 times, but after that a bit monotonous. The

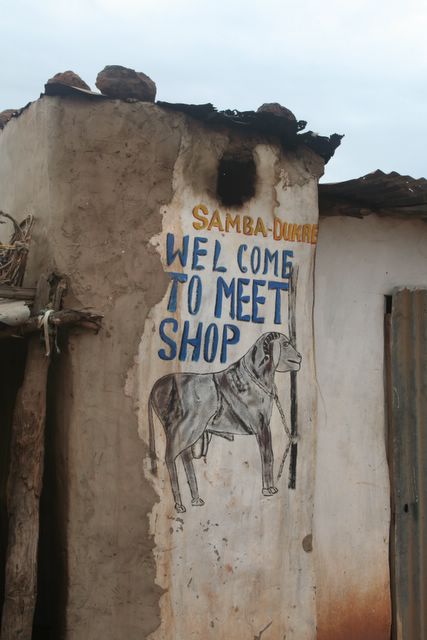

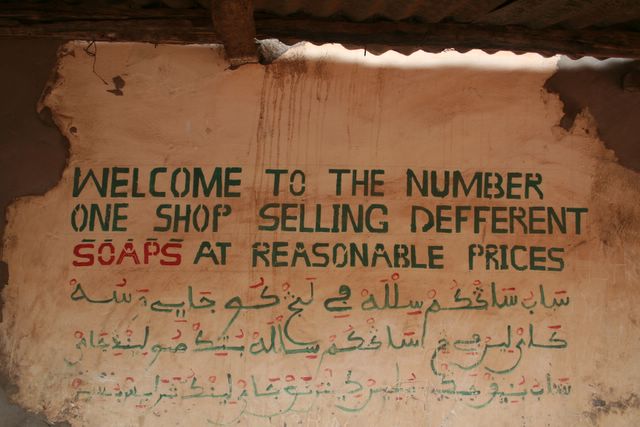

Gambia, just over 300 kilometers in length and never more than 50

kilometers from north to south, slices through Senegal and takes its

name from the river it surrounds. This tiny English-speaking

country is a popular destination with British package tourists escaping

the drab winter back home. If you confined yourself to the 10

kilometer beach strip where the hotels, restaurants and bars are all

congregated, you would certainly have the impression that the country

was fairly well-off. Venture further inland and another side

of Gambia unfolds. The country is poor, even by African

standards and the people are struggling to make ends meet. Basic

goods are not cheap and there's little on offer in the local markets--

sweet potatoes sold in piles of three or four, a few onions, some

okra and perhaps an over-priced aubergine or two if you're lucky.

Pasta is sold in minuscule quantities, the smallest bag can't be

more than 25 grams. Even bananas are

The

Gambia, just over 300 kilometers in length and never more than 50

kilometers from north to south, slices through Senegal and takes its

name from the river it surrounds. This tiny English-speaking

country is a popular destination with British package tourists escaping

the drab winter back home. If you confined yourself to the 10

kilometer beach strip where the hotels, restaurants and bars are all

congregated, you would certainly have the impression that the country

was fairly well-off. Venture further inland and another side

of Gambia unfolds. The country is poor, even by African

standards and the people are struggling to make ends meet. Basic

goods are not cheap and there's little on offer in the local markets--

sweet potatoes sold in piles of three or four, a few onions, some

okra and perhaps an over-priced aubergine or two if you're lucky.

Pasta is sold in minuscule quantities, the smallest bag can't be

more than 25 grams. Even bananas are  sometimes

hard to come by.

Amadou, a newly-qualified and highly-motivated teacher who

invited us to have a rest and a look at his school, can barely get by

on his monthly salary of 1,800 Dalasis (approx. 50 euros) and farmers

find it hard to pay for goods such as soap, gas and cooking oil.

On a more positive note, school fees for girls have been

abolished which means education is now more accessible than ever for

females in the country. NGOs abound, new schools are being

constructed and safe drinking water is readily available from the town pump or well even in the smallest of

villages.

sometimes

hard to come by.

Amadou, a newly-qualified and highly-motivated teacher who

invited us to have a rest and a look at his school, can barely get by

on his monthly salary of 1,800 Dalasis (approx. 50 euros) and farmers

find it hard to pay for goods such as soap, gas and cooking oil.

On a more positive note, school fees for girls have been

abolished which means education is now more accessible than ever for

females in the country. NGOs abound, new schools are being

constructed and safe drinking water is readily available from the town pump or well even in the smallest of

villages. Cycling the south bank road we attracted the usual swarms of youngsters

waving wildly after the toubabs and

hoping for some handouts--money being top on the wish list.

Riding along dodging the potholes also turned out to be a good

way to

get to know Gambians as the roads are busy with children on their way

to school, groups of women filing past balancing loads of wood or

buckets of water on their head, and men going off to work.

We got a first hand glimpse of life in the countryside when the

head of a roadside village invited us to spend the night in his

compound. The chief is a man of 80 who lives with his extended

family--about 100 people in all we were told--in a series of mud-brick

dwellings surrounding a central courtyard. There was a flurry of

activity upon our arrival as the men concurred as to where to lodge us,

children scurried off to fetch buckets of water and the women rushed

about rustling up a meal for us. The villagers were truly

hospitable and we were mighty thankful for a roof over our heads when a

violent storm broke out in the wee hours of the morning. The next

evening we were again saved from a wet night in the tent (no hotels in

the vicinity) when a schoolboy, Moutar, invited us to stay with his

family. Their compound was simple and lacked the few 'luxuries'

of the chief's. There was no radio or kerosene lamp and the

children were running around in rags. Nevertheless, the family

had somehow found the money to pay Moutar's school fees, there was

abundant rice and fish and lots of laughter.

Cycling the south bank road we attracted the usual swarms of youngsters

waving wildly after the toubabs and

hoping for some handouts--money being top on the wish list.

Riding along dodging the potholes also turned out to be a good

way to

get to know Gambians as the roads are busy with children on their way

to school, groups of women filing past balancing loads of wood or

buckets of water on their head, and men going off to work.

We got a first hand glimpse of life in the countryside when the

head of a roadside village invited us to spend the night in his

compound. The chief is a man of 80 who lives with his extended

family--about 100 people in all we were told--in a series of mud-brick

dwellings surrounding a central courtyard. There was a flurry of

activity upon our arrival as the men concurred as to where to lodge us,

children scurried off to fetch buckets of water and the women rushed

about rustling up a meal for us. The villagers were truly

hospitable and we were mighty thankful for a roof over our heads when a

violent storm broke out in the wee hours of the morning. The next

evening we were again saved from a wet night in the tent (no hotels in

the vicinity) when a schoolboy, Moutar, invited us to stay with his

family. Their compound was simple and lacked the few 'luxuries'

of the chief's. There was no radio or kerosene lamp and the

children were running around in rags. Nevertheless, the family

had somehow found the money to pay Moutar's school fees, there was

abundant rice and fish and lots of laughter.  After

our tour of The Gambia, we crossed back into Senegal and the

picturesque, but troubled Casamance region. Humidity was high and the

tension palpable as we cycled through the forests of hardwood trees and

past emerald green rice fields to reach Ziguinchor. Once Senegal's

leading tourist area, rebel activity and sporadic fighting have

kept visitors away in recent years. We were told the area is calm

at the moment, but truckloads of nervous-looking soldiers poised for

action and tanks rolling past put us off from exploring the backroads.

After

our tour of The Gambia, we crossed back into Senegal and the

picturesque, but troubled Casamance region. Humidity was high and the

tension palpable as we cycled through the forests of hardwood trees and

past emerald green rice fields to reach Ziguinchor. Once Senegal's

leading tourist area, rebel activity and sporadic fighting have

kept visitors away in recent years. We were told the area is calm

at the moment, but truckloads of nervous-looking soldiers poised for

action and tanks rolling past put us off from exploring the backroads.While the past month has been devoid of 'attractions and highlights', it has been a good introduction to Africa and its people. We have found the locals to be kind, friendly and exceedingly optimistic in spite of conditions that are sometimes appalling. Africans are also a people on the move. We've met Mauritanian shopkeepers in The Gambia, a woman from Sierra Leone tending a restaurant in Banjul, a

Nigerian

man selling his art in St. Louis and countless others who have worked

outside of their home countries, all hoping to better their situations.

One afternoon in Banjul Eric even ran into a young Gambian he had

met

a month back in Mauritania's northern city, Nouadhibou. The man

had come north looking for work and then got stuck toiling as fisherman

when his money ran out. He was hard up and couldn't afford the

trip back home. Fortunately for him, when election time in

the Gambia rolled around the president sent three buses up to

Mauritania to bring back the voters free of charge. These kinds of

chance encounters, rather than imposing monuments and temples, have

made the month memorable.

Nigerian

man selling his art in St. Louis and countless others who have worked

outside of their home countries, all hoping to better their situations.

One afternoon in Banjul Eric even ran into a young Gambian he had

met

a month back in Mauritania's northern city, Nouadhibou. The man

had come north looking for work and then got stuck toiling as fisherman

when his money ran out. He was hard up and couldn't afford the

trip back home. Fortunately for him, when election time in

the Gambia rolled around the president sent three buses up to

Mauritania to bring back the voters free of charge. These kinds of

chance encounters, rather than imposing monuments and temples, have

made the month memorable. Tomorrow we'll take to the road again and have a chance to brush up on our limited Portuguese as we spend a few days in Guinea Bissau. Then it will be on to Guinea where we hope to find more plentiful fruit and vegetables and also more strenuous cycling as we tackle the hills of the spectacular Fouta Djalon region. The roads there--often no more than dirt tracks--are said to be unpassable in the rainy season which is just winding down. Let's hope for dry weather!