update 32.

desert detour

Cycling in Egypt

26 January 2009

Total kilometers cycled: 48,536

Specific country info on routes & roads/food & accommodation/the locals available here.

"Welcome

to Egypt. Passport, please," came the mumbled request from

the

young soldier whose lit cigarette dangled casually from his mouth.

"Welcome

to Egypt. Passport, please," came the mumbled request from

the

young soldier whose lit cigarette dangled casually from his mouth.I smiled the same ingratiating smile I'd been using since I first entered Africa more than two years earlier.

"Here you are, sir."

He thumbed slowly through the pages and then looked up, "Country?"

"France."

"Where going?"

"Kom Ombo." I reeled off the name of a well-known tourist site some 60 kilometers up the road.

"You go in convoy. Wait here."

No, not the dreaded convoy. Egypt is well-known for its obsession with 'security' and cyclists are regularly forced to hop on the back of a truck 'for their own safety'. Bumping along with a bunch of Kalashnikov-armed soldiers wasn't the way I envisioned ending my Africa tour.

Eric shot me a glance that conveyed his accumulated exasperation with the authorities.

"Waiting not possible. We go Cairo." I found myself speaking in the pidgin English that I normally found so insulting.

The young man conferred with his colleagues, of which there were many. Egypt is said to have 6 police officers for every inhabitant.

"You go Cairo, on bicycle?" A circle had now formed around us. A few men were pointing at the map and making out the English names, slowly and deliberately like a school child learning phonics. Inevitably curiosity got the best of one policeman and he reached over and gave my hot-pink horn a loud honk. This brought on hoots of laughter from the rest of the bystanders. Checkpoint duty was obviously not for the most capable within Egypt's security forces.

Again I smiled. This time with indulgence at their antics.

"Yes, we go now. Cairo very far. No waiting convoy."

And to our great surprise the

soldiers waved us on.

And to our great surprise the

soldiers waved us on.Unfortunately, our feeling of triumph didn't last long because we soon spied the truckload of soldiers tailing us from a not too discrete distance. Did they have nothing better to do? Track down terrorists? Ferret out subversives? Chase pickpockets? I guess not. The only thing that got them off our tails was their addiction to tea-drinking. Praying was just a minor interruption. They would pull over, whip out the prayer rugs and be back on our trail within minutes.

We'd heard the only way to avoid having a personal escort through Egypt was to leave the heavily populated Nile route and head into the desert--our old friend the Sahara. We'd already cycled 2,000 kilometers through the world's largest desert at the beginning of the tour, through Western Sahara and Mauritania.

Deserts are inhospitable places. Distances between settlements are long, water is scarce, and winds are fierce. Before setting out from Luxor for the 1,300 kilometer ride through the Western Desert to Cairo, we sought out advice and information. A posting to a cyclist's forum got this response:

The only water sources available are at or very close to the oases, none between them. The distances are 200-300 kilometers.

But Saliva, a Spaniard we'd been in contact with who had done the route a year earlier, replied to our email saying:

There are checkpoints every 60

kilometers or so.

There are checkpoints every 60

kilometers or so. What to believe? Salva is a real

adventurer--he's just cycled through Afghanistan.

But surely the locals knew what they were talking about.

What to believe? Salva is a real

adventurer--he's just cycled through Afghanistan.

But surely the locals knew what they were talking about.We were keen to get back on the road again--having tired at marveling at the running water in our guest house--and decided to set off without any further route information. If Salva had managed, we were sure that we too would somehow survive.

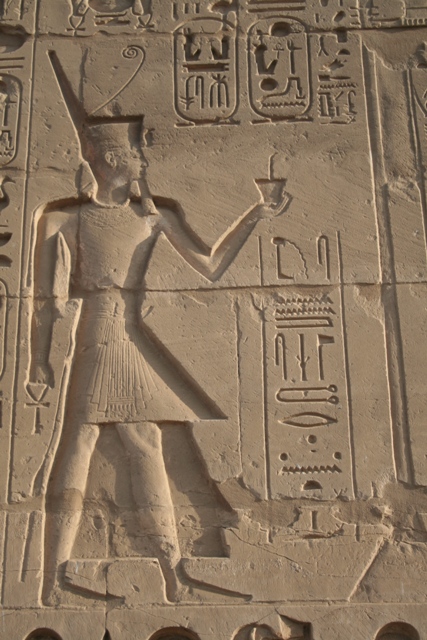

Just after sunrise we rode past the magnificent Luxor Temple, along the lush banks of the Nile until the road took a sharp turn into the open desert and signs of civilization started to disappear. 40 kilometers down. So far, so good. A truck stop with restaurant and water. Using a combination of sign language and the few Arabic words we knew, we attempted to find out far it was to the next water source. 250 kilometers was the unsatisfactory answer we received from the man who sold us the over-priced snacks. We tried a wise-looking truck driver and he gave us the same response. A well-dressed gentleman in a flashy 4WD also insisted that the first available water source would be in the oasis town of El Kharga 250 kilometers away.

With all our water bottles full, we were only carrying 10 liters of water between the two of us--hardly enough for two days in the desert even in the cool winter weather.

But

experience had taught us that rarely are vast expanses of land truly

empty. There's always something out there. A

ranger's

bungalow, a mining camp, a manned antenna. Or generous

motorists

with water to spare.

But

experience had taught us that rarely are vast expanses of land truly

empty. There's always something out there. A

ranger's

bungalow, a mining camp, a manned antenna. Or generous

motorists

with water to spare.And so we set off into the uncertainty of the desert with our ten liters of water, 15 packs of instant noodles, two cans of quick cooking oats, a dozen pita breads, three boxes of Laughing Cow cheese wedges, two tins of tuna imported from Thailand, a family-sized jar of strawberry jam and a handful of tomatoes Eric had nicked off a passing truck. Our throats might be parched, but our stomachs would be full.

After 55 angst-filled kilometers, a cluster of

buildings appeared on

the horizon. A police checkpoint. Very friendly

guys who

were obviously bored stiff stuck out in the desert taking down license

plate numbers and asking tourists which country they are from.

They became our friends and allies over the next ten days and

we

came to count on finding their stations ever 60 kilometers or so, just

as Salva had said. They made us sweet chai and filled our

water

bottles, offered us bread when our supplies were running low and even

gave

us a 6 kilometer lift to their station when they found us huddled next

to a sand dune taking cover from the gusting headwind.

After 55 angst-filled kilometers, a cluster of

buildings appeared on

the horizon. A police checkpoint. Very friendly

guys who

were obviously bored stiff stuck out in the desert taking down license

plate numbers and asking tourists which country they are from.

They became our friends and allies over the next ten days and

we

came to count on finding their stations ever 60 kilometers or so, just

as Salva had said. They made us sweet chai and filled our

water

bottles, offered us bread when our supplies were running low and even

gave

us a 6 kilometer lift to their station when they found us huddled next

to a sand dune taking cover from the gusting headwind. Sometimes

amazingly beautiful, often distressingly boring, the desert

was above all a chance to reflect on the thousands of

kilometers

we'd pedaled through Africa. Just north of Farafra we camped

amidst the eerie arctic-like rock formations of the White Desert.

I was awed by their beauty and felt truly thankful

to have

the freedom to explore the wonders of our planet. During

the

night a bitter wind began pounding us from the north. The

next

day we struggled to move at 10 Kilometers per hour, knowing that some

700 kilometers of desert lay ahead. At one point the

relentless

whistling of the wind almost drove Eric over the edge.

Sometimes

amazingly beautiful, often distressingly boring, the desert

was above all a chance to reflect on the thousands of

kilometers

we'd pedaled through Africa. Just north of Farafra we camped

amidst the eerie arctic-like rock formations of the White Desert.

I was awed by their beauty and felt truly thankful

to have

the freedom to explore the wonders of our planet. During

the

night a bitter wind began pounding us from the north. The

next

day we struggled to move at 10 Kilometers per hour, knowing that some

700 kilometers of desert lay ahead. At one point the

relentless

whistling of the wind almost drove Eric over the edge. "I can't take it any more. There's no point in continuing like this. Let's just get on a f****** truck," he shouted, jumping up and down and shaking his fists like a madman. I gave him the MP3 player, hoping a bit of Fleetwood Mac would calm his nerves.

For

me, a truck to Cairo was unthinkable. How could I possibly

give

up when the end was so near? I spurred myself on by thinking

of

Alastair Humphreys cycling through sub-zero temperatures in Siberia.

A headwind in the desert was nothing in comparison.

For

me, a truck to Cairo was unthinkable. How could I possibly

give

up when the end was so near? I spurred myself on by thinking

of

Alastair Humphreys cycling through sub-zero temperatures in Siberia.

A headwind in the desert was nothing in comparison. Our

last night in the desert we spread out our mats in the operating room

at one of the many ambulance centers. It was an odd feeling

to

sleep next to the gurneys and sterilized instruments and we were

thankful our rest wasn't interrupted by accident victims being brought

in to be stitched up.

Our

last night in the desert we spread out our mats in the operating room

at one of the many ambulance centers. It was an odd feeling

to

sleep next to the gurneys and sterilized instruments and we were

thankful our rest wasn't interrupted by accident victims being brought

in to be stitched up.In the morning a thick fog enveloped the highway and we could hear the convoys of slow-moving lorries creeping along well before their headlights came into view. That was scary but worse awaited. Cycling in central Cairo is almost tantamount to signing a suicide note. Six lane highways turn into a jumble of congested roads snaking through the city. Playing chicken is the norm and the only recognizable traffic rule is continuous honking. My whistle and flimsy neon-pink horn didn't seem to make a dint in the Cairo mayhem, where living in the center of the city is akin to living inside a factory in terms of noise levels. I shouted at the taxis who cut me off, cursed the scooters that came careening past me on the elevated roads and made wild hand signals imploring drivers to give me the right of way. Eric, on the other hand, swerved in and out of traffic with such ease that you'd think his former profession had been a New York City bicycle courier. Fortunately the cycling gods where watching over us and we made into the city with nothing more serious than frayed nerves.

After a few days seeing the sights--Egyptian Museum and Islamic Cairo--we decided our lungs needed a break from the choking air pollution, which according to the WHO is 20 times above the acceptable level, having the same effect as smoking a pack of cigarettes a day. We left the blaring horns and crowded streets of central Cairo for the bizarre suburb of El Rehab. More than a gated community, El Rehab is more like a walled city that has been plopped down in the desert. It's suburbia gone awry and the cookie-cutter villas, pastel apartment blocks and food court boasting McDonalds, KFC and Hardees could be most anywhere on the planet. Headscarves and the melodic calls to prayer are the only indications that El Rehab is located somewhere in the Muslim world. A little sterile for our tastes, but ideal for taking care of some mundane tasks--contacting the bank, renewing insurance, doing some bike maintenance and trying to get the computer fixed.

Egypt marks the end of our Africa expedition, but not the end of World Biking. Next up is the Middle East, then it's on to Turkey, into Eastern Europe and back to France mid-May, Insha'Allah.

contact us at: worldbiking@gmail.com

Support our chosen charity and help educate girls in Africa-more info here