update 17.

living on africa time

27 July - 4 September 2007

Total kilometers cycled: 25,887

Burundi,Tanzania and Malawi

Specific country info on routes & roads/food & accommodation/the locals available here.

After 15 months on the road, the pace is slowing and we're finding it easier and easier to conjure up excuses for hanging around 'just one more day' when we stumble upon a nice spot for a rest. Comfy couches at backpackers hostels, warm showers, Shoprite supermarkets and a decent selection of books are all too alluring after so many months of rest houses cum brothels where murky water for bathing comes in a bucket, kerosene lamps provide light and 'the toilet' is of the long-drop variety--a crudely cut hole, often not larger than a grapefruit, where one must squat and take aim. We'll have to pick up the pace if we want to avoid the sweltering summer heat of the Namib desert and make it to Cape Town before the Christmas rush to the coast. In

Burundi we were welcomed with wide, toothy smiles and exuberant

greetings from the locals who were unused to seeing foreigners after

more than a decade of armed conflict that all but killed tourism in

this tiny land-locked country. The steep climbs we had come to know

(and dread!) in Rwanda continued. Fortunately, there always

seemed to be gaggles of energetic kids willing to push us for

kilometers through the heavily-terraced countryside and fragrant

forests of eucalyptus and then watch us swoosh down the descents,

obviously proud of their efforts. The roads buzzed with activity and

nothing was deemed too large or cumbersome to fit on the back of a

bicycle. Bike-pooling was the norm with two and sometimes

three

passengers squeezing onto the back rack and occasionally a small

child teetering on the handle bars. Only a foolish

Mzungu

would peddle

up the hills--clued-in locals always latched on to a passing truck and

hitched a ride up the torturous mountains.

In

Burundi we were welcomed with wide, toothy smiles and exuberant

greetings from the locals who were unused to seeing foreigners after

more than a decade of armed conflict that all but killed tourism in

this tiny land-locked country. The steep climbs we had come to know

(and dread!) in Rwanda continued. Fortunately, there always

seemed to be gaggles of energetic kids willing to push us for

kilometers through the heavily-terraced countryside and fragrant

forests of eucalyptus and then watch us swoosh down the descents,

obviously proud of their efforts. The roads buzzed with activity and

nothing was deemed too large or cumbersome to fit on the back of a

bicycle. Bike-pooling was the norm with two and sometimes

three

passengers squeezing onto the back rack and occasionally a small

child teetering on the handle bars. Only a foolish

Mzungu

would peddle

up the hills--clued-in locals always latched on to a passing truck and

hitched a ride up the torturous mountains.

Just before entering Burundi a BBC World Service report informed us that the leader of the only remaining rebel faction had walked out of peace talks in Bujumbura, and, although his whereabouts were unknown, it was hoped that he would soon return to the capital. With this in mind, we weren't sure whether the groups of bored-looking and well-armed soldiers lounging under trees every few kilometers alongside the road leading to the capital should alarm or comfort us. The guest house owner assured us that there would be no trouble, the rebels were 'far away'' yonder hiding out in those low-lying hills.

We arrived safe and sound in low-key Bujumbura, treated ourselves to cakes at the Kappa bakery, rode out past the sprawling UN Peacekeepers camp and went for a swim in the turquoise waters of Lake Tanganyika. Despite 90% of the population reportedly living on less than $1 a day and virtually no tourists, Bujumbura had a surprisingly good range of restaurants and we splashed out on a mushroom pizza for dinner (we've surely long ago reached our lifetime threshold of rice and beans). Of course there were few locals eating at the restaurant. Most of the other diners were expats, in some way attached to the aid industry. They arrived in shiny new white Land Rovers driven by a local man--always one of the best educated as jobs with an NGO are highly-prized- and didn't gasp at the prices like we did. We are pleased to report that we've never seen a white Land Rover with Camfed on the side and you can rest assured that your donations are going to help educate girls and not to foot the bill for the extravagant lifestyle of some career 'aid worker'.

Our

original plan was to have one last adventure and cross remote Western

Tanzania entirely by bicycle. We came to our senses after

speaking with an ex pat who had done the 600-odd kilometer dirt-track

journey in a convoy of three Land Rovers and claimed that

unbelievably deep sand and a very rutted and rough road meant he had

progressed not more than 100 kilometers on some days. Being

stranded in the bush forced to dig for water in dry-river beds doesn't

rank high on our 'must do' list so we opted instead for a voyage on the

aging MV Liemba.

Our

original plan was to have one last adventure and cross remote Western

Tanzania entirely by bicycle. We came to our senses after

speaking with an ex pat who had done the 600-odd kilometer dirt-track

journey in a convoy of three Land Rovers and claimed that

unbelievably deep sand and a very rutted and rough road meant he had

progressed not more than 100 kilometers on some days. Being

stranded in the bush forced to dig for water in dry-river beds doesn't

rank high on our 'must do' list so we opted instead for a voyage on the

aging MV Liemba. This

German-built ship has been plying the waters of Lake Tanganyika for

more than 80 years, serving the small lakeside fishing villages that

would otherwise almost be cut-off from the rest of the country.

Since there are only three real ports along the way, small boats

carrying goods and passengers come out to meet the ship when it docks

off shore. There's a frenzy of activity, day and night, as

passengers heave themselves out of the boats and then shimmy up the

railings and onto the ship. Everything from satellite dishes to 50 kilo

sacks of sardines somehow make it on and off the small boats as they

bob up and down in the often turbulent waters.

This

German-built ship has been plying the waters of Lake Tanganyika for

more than 80 years, serving the small lakeside fishing villages that

would otherwise almost be cut-off from the rest of the country.

Since there are only three real ports along the way, small boats

carrying goods and passengers come out to meet the ship when it docks

off shore. There's a frenzy of activity, day and night, as

passengers heave themselves out of the boats and then shimmy up the

railings and onto the ship. Everything from satellite dishes to 50 kilo

sacks of sardines somehow make it on and off the small boats as they

bob up and down in the often turbulent waters.After two nights aboard the ship, we arrived in Kasanga and faced a 300-kilometer stretch of unpaved roads. On our three-day ride we encountered all the usual obstacles: knee-deep sand , bumpy corrugations prone to inducing early arthritis, and the ever-present predatory drivers. Eric gave one of these maniacs the finger after he nearly grazed us when he sped by in a cloud of dust. To our surprise, the man behind the wheel screeched to a halt and put his vehicle in reverse. Fearing there might be bloodshed, Amaya pedaled off in a flurry. Eric held his ground and was in fact greeted by a friendly family of Tanzanians who mistakenly thought he was signaling for help.

The

last rains had fallen months ago and the land was parched and cracking.

When the sun rose high in the sky it was scorching hot, but

evenings and early mornings were downright cold and bathed in soft

pinks and brilliant orange light. When no accommodation was

available we explained our mission to the headman of a village and

asked for permission to camp, just as we have done in many other parts of Africa. Later we saw travel

agencys offering 4-hour cultural tours of 'authentic

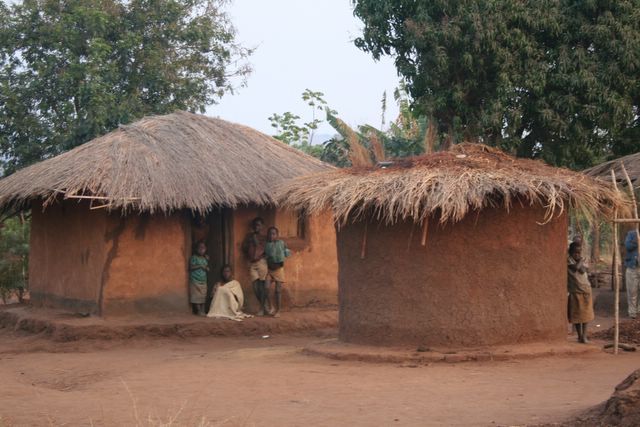

The

last rains had fallen months ago and the land was parched and cracking.

When the sun rose high in the sky it was scorching hot, but

evenings and early mornings were downright cold and bathed in soft

pinks and brilliant orange light. When no accommodation was

available we explained our mission to the headman of a village and

asked for permission to camp, just as we have done in many other parts of Africa. Later we saw travel

agencys offering 4-hour cultural tours of 'authentic

villages' for

$25 a pop. And imagine, we got to stay in the villages for free and

were treated like honored guests.

In comparison with a busy western lifestyle filled with long

hours at the office, regular visits to a sports clubs to keep the

ever-expanding rear end in check, loads of activities designed to

provide fulfillment and relaxation plus unlimited entertainment

options, life in an African village appears quite simple. A woman's day

revolves around

preparing food, minding children,keeping the hut tidy, fetching water

and firewood and doing small-scale farming. Men

are responsible for transporting large loads on

bicycles, building fences and huts, and some of the heavier farming

tasks. They have much more leisure time and like to gather under

trees to play some

sort of complicated-looking game with marbles and chat with their

friends. Everyone rises by dawn and a few hours after sunset

villages usually go quiet. Thin mats are rolled out onto the

floor and everyone drops off to sleep. Entertainment is hanging

out on a rickety wooden bench in front of the local shop and maybe

splurging on a bottle of warm coca-cola. Somebody might be lucky enough

to have a radio which inevitably belches out more static than music.

Sunday is a day of rest and religion and for males, bouts of drinking

the potent local brew. The routine is broken up by visits to

relatives in neighboring villages and maybe an occasional trip into the

nearest town to stock up on supplies. Certainly we

couldn't bear such a lifestyle lacking in western-style comforts and diversions for too long, but

most villagers we meet seem to be quite content with their lives.

villages' for

$25 a pop. And imagine, we got to stay in the villages for free and

were treated like honored guests.

In comparison with a busy western lifestyle filled with long

hours at the office, regular visits to a sports clubs to keep the

ever-expanding rear end in check, loads of activities designed to

provide fulfillment and relaxation plus unlimited entertainment

options, life in an African village appears quite simple. A woman's day

revolves around

preparing food, minding children,keeping the hut tidy, fetching water

and firewood and doing small-scale farming. Men

are responsible for transporting large loads on

bicycles, building fences and huts, and some of the heavier farming

tasks. They have much more leisure time and like to gather under

trees to play some

sort of complicated-looking game with marbles and chat with their

friends. Everyone rises by dawn and a few hours after sunset

villages usually go quiet. Thin mats are rolled out onto the

floor and everyone drops off to sleep. Entertainment is hanging

out on a rickety wooden bench in front of the local shop and maybe

splurging on a bottle of warm coca-cola. Somebody might be lucky enough

to have a radio which inevitably belches out more static than music.

Sunday is a day of rest and religion and for males, bouts of drinking

the potent local brew. The routine is broken up by visits to

relatives in neighboring villages and maybe an occasional trip into the

nearest town to stock up on supplies. Certainly we

couldn't bear such a lifestyle lacking in western-style comforts and diversions for too long, but

most villagers we meet seem to be quite content with their lives.After climbing 35 kilometers over a torturous 2,500 meter pass, our last stop in Tanzania was the picturesque town of Tukuyu, surrounded by rolling hills covered with tea plantations. We had meant to spend just one night before swooping down to Malawi, but a case of nasty saddle sores kept us almost a week. The elderly doctor at the government hospital was keen to 'operate' , but, given the sensitive location of the inflammation, Eric balked away from potentially being butchered by a slip of the knife. A course of antibiotics and a good deal of squeezing eventually did the trick.

So with a slight delay we made it to Malawi and got down to the serious business of relaxing. Like many travelers before us, we were seduced by the beauty of the lake and the laid-back atmosphere of the lodges dotting its shores. Nkhata Bay is almost an obligatory stop on the overland circuit and we spent several days there lazing on the rocky beach, snorkeling, raiding the bookshelves of the guesthouse and trying to get some decent photos of the sunrise. Each evening the lake was lit up by the parafin lamps of fisherman in dugout canoes. These men cast their nets under moonlight and paddle back to shore just as the sun is rising. Dickens was one such fisherman we met when a puncture brought us to his small

village along the main

lakeshore highway. He immediately approached us offering assistance and

sending off a child to fetch water so we could test our inner tube.

He was particularly articulate and we at first assumed he was the

village teacher which brought out a small chuckle from the bystanders.

No, no he assured us, just a simple fisherman. He would have

liked to continue his studies, he explained, but his father had died

and his mother's meager earnings from selling vegetables weren't enough

to keep the family afloat. He didn't earn much either, perhaps a

100 Kwacha (80 cents) a day, but it was enough to buy sugar, soap,

batteries for his radio and school uniforms for his 3 younger siblings.

He was frustrated though and didn't see how life would ever get

any better for his village. They were forgotten he said.

They did have a pump now in the village which made life much

easier, especially for the women, but there was still no electricity and

never any visits from government officials or NGOs. He wasn't

really complaining about his life. In general, Africans are

resilient people who will make the best of the lot they've drawn in

life without whining about their circumstances. He only wanted

more than his village had to offer.

village along the main

lakeshore highway. He immediately approached us offering assistance and

sending off a child to fetch water so we could test our inner tube.

He was particularly articulate and we at first assumed he was the

village teacher which brought out a small chuckle from the bystanders.

No, no he assured us, just a simple fisherman. He would have

liked to continue his studies, he explained, but his father had died

and his mother's meager earnings from selling vegetables weren't enough

to keep the family afloat. He didn't earn much either, perhaps a

100 Kwacha (80 cents) a day, but it was enough to buy sugar, soap,

batteries for his radio and school uniforms for his 3 younger siblings.

He was frustrated though and didn't see how life would ever get

any better for his village. They were forgotten he said.

They did have a pump now in the village which made life much

easier, especially for the women, but there was still no electricity and

never any visits from government officials or NGOs. He wasn't

really complaining about his life. In general, Africans are

resilient people who will make the best of the lot they've drawn in

life without whining about their circumstances. He only wanted

more than his village had to offer. Our

only

strenuous cycling was a trip up the escarpment to Livingstonia to visit

the

the old colonial buildings and hospital. The gravel road up consists of

20 hairpin bends and with little traction, we had to resort to pushing on the steepest

turns. This was the site of our first clothing casualty as the

sole of Amaya's left shoe detached itself from the upper. Several

days were spent riding with a sandal on the left foot and a shoe on the

right. Nobody looked at her oddly, in fact maybe they thought she

was making a fashion statement. After all, we'd seen two women

sharing a pair of shoes, one wearing the left and the other the right

with each having one foot bare. Why not try mix and match?

Our campsite on the escarpment was one of the most spectacular of

the entire trip. We could look out over the slate-blue mountains

and down on the sparkling lake below, we just had to watch our step

lest we plunge over the edge.

Our

only

strenuous cycling was a trip up the escarpment to Livingstonia to visit

the

the old colonial buildings and hospital. The gravel road up consists of

20 hairpin bends and with little traction, we had to resort to pushing on the steepest

turns. This was the site of our first clothing casualty as the

sole of Amaya's left shoe detached itself from the upper. Several

days were spent riding with a sandal on the left foot and a shoe on the

right. Nobody looked at her oddly, in fact maybe they thought she

was making a fashion statement. After all, we'd seen two women

sharing a pair of shoes, one wearing the left and the other the right

with each having one foot bare. Why not try mix and match?

Our campsite on the escarpment was one of the most spectacular of

the entire trip. We could look out over the slate-blue mountains

and down on the sparkling lake below, we just had to watch our step

lest we plunge over the edge.It's been a restful month, but our Malawian holiday is coming to a close and tomorrow we head off towards Zambia. We've finally traded in our East Africa Lonely Planet for Southern Africa so the end is drawing near...if we get a move on that is and get down to the serious business of cycling.

contact us at: worldbiking@gmail.com

Support our chosen charity and help educate girls in Africa-more info here